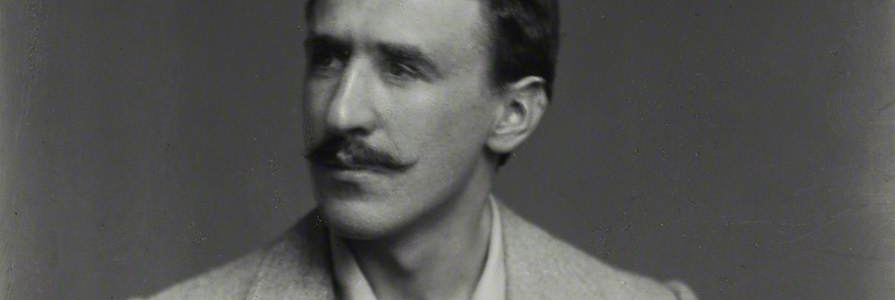

Charles Rennie Mackintosh – A Visionary of Art and Architecture

Unveiling the Life and Legacy of an Icon

In the annals of design and architecture, few names carry the weight and prestige of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. This Scottish architect, designer, and artist, born in 1868 in Glasgow, left an indelible mark on the world of art, architecture, and interior design. Mackintosh’s legacy, defined by his distinctive style and pioneering spirit, continues to influence and inspire generations of designers and creatives worldwide.

The Early Years

Mackintosh’s artistic journey began at a young age. Recognizing his innate talent, he enrolled at the Glasgow School of Art in 1884. It was at this institution that his creative genius started to flourish, and his lifelong commitment to the world of art and design took root.

The Glasgow Style

Mackintosh’s work is synonymous with the “Glasgow Style,” a design movement that swept through the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This style was characterized by its emphasis on simplicity, clean lines, and the integration of botanical and geometric motifs. The Glasgow Style marked a departure from the ornate, heavily ornamented designs of the Victorian era, and Mackintosh emerged as one of its most prominent figures.

Architectural Marvels by Mackintosh

Mackintosh’s architectural creations have become emblematic of his innovative spirit. One of his most celebrated works is the Glasgow School of Art. Completed in two phases (1897-1899 and 1907-1909), the building is a masterpiece of modern architecture. It demonstrates Mackintosh’s innovative use of materials, inventive spatial design, and an overarching focus on functionality.

The Willow Tea Rooms, another iconic Mackintosh project, showcases his unique design principles. Collaborating with businesswoman Kate Cranston, he created a space that was not just for refreshments but a complete sensory experience. The tearooms feature geometric patterns, high-backed chairs, and stylized floral motifs, making them a visual and cultural delight.

Hill House, designed for publisher Walter Blackie in Helensburgh, Scotland, is another architectural gem in Mackintosh’s portfolio. It combines his keen eye for interior design and his architectural vision. Hill House is a testament to his ability to create a harmonious environment, both inside and out.

Innovative Furniture and Interior Design

Mackintosh’s influence extended beyond architecture. He was a pioneer of modern interior design, creating furniture and lighting that were both functional and visually striking. His furniture designs often featured geometric shapes, asymmetry, and unique details. Pieces, like the high-backed chairs and elegant tables, have become classics in the world of design. These designs continue to be reproduced and appreciated today.

Later Life and the Legacy of Mackintosh

While Mackintosh enjoyed a period of recognition and success, he faced professional challenges in his later years. These challenges led him to move to the South of France with his wife, Margaret Macdonald, also an artist and collaborator on many of his projects. Mackintosh continued to paint and create during this time, but his architectural career faced a decline.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh passed away in 1928, but his legacy lived on. In the mid-20th century, there was a resurgence of interest in his work, and he was posthumously recognized for his groundbreaking contributions to the worlds of design and architecture.

Today, Mackintosh’s work remains as relevant and inspirational as ever. His designs, marked by their originality and aesthetic appeal, continue to captivate architects, designers, and art enthusiasts. His influence is most palpable in Glasgow, where his architectural and design legacy is an integral part of the city’s cultural identity.

In an era when art and functionality often intersect, Mackintosh’s creative spirit and visionary work serve as a testament to the power of innovation and the enduring legacy of a design genius. From the Glasgow School of Art to the Willow Tea Rooms, and the multitude of furniture and interior designs that bear his signature, Mackintosh’s work stands as a living testament to his unparalleled impact on the world of design and architecture.

Mackintosh Inspired Glass Panels

Leadbitter Glass creates bespoke decorative glass panels for windows and doors in a Mackintosh style. Browse our vast galleries to find a design for your home. We can also create unique Mackintosh themed glass from your drawings or even jewelry.